The rules to follow when you write stories

There's no hard and fast rule laying down how you should begin a work of fiction, except for perhaps one: get the reader involved in the story as soon as possible.

Jim Thompson was a master at that.

You can open just about any Jim Thompson novel on the first page and find yourself drawn into his tale by the second sentence, sometimes even the first.

E.g.:

"I'd gotten out of my car and was running for the porch when I saw her. She was peering through the curtains of the door, and a flash of lightning lit up the dark glass for an instant, framing her face like a picture..."

(The opening of A Hell of a Woman by Jim Thompson).

Having said that, there are writers who've flouted that rule from time to time, indeed every rule going, and still produced amazingly readable works.

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov is an astounding comic novel in which even the index is funny. It's written in the form a review of a poem. The reviewer takes centre stage in his purported appraisal of the work of the poet, and he finds excuses in every line of the poet's magnum opus to discuss his own life story.

Borges uses a similar idea for his short story Pierre Menard, author of the Quixote.

This story envisages an author re-writing Don Quixote without changing a single word of it, and being credited with having created a better and more original novel than Cervantes.

Nabokov and Borges both adopt the persona of a bumptious literary critic for their works. This approach doesn't lend itself to an opening in which the reader is taken effortlessly to the meat of the story. But this hardly matters. These are works of genius that turn storywriting on its head and do it so successfully that you can only marvel at what the authors have achieved.

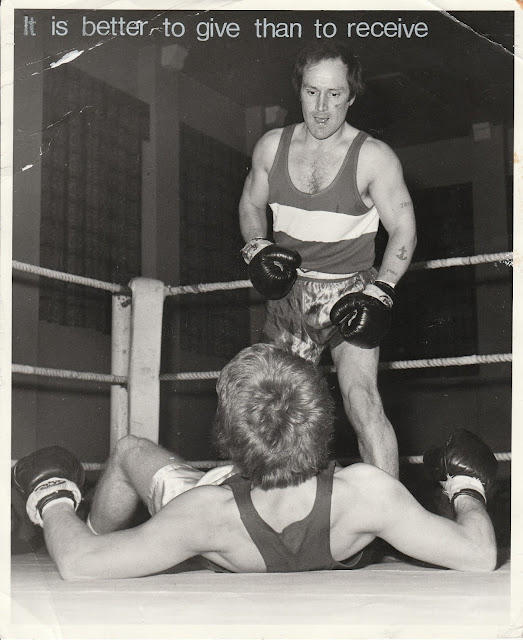

The take-home is this: when you're that good, the only rule that counts is that there are no rules.

See:

Do you want to write a story?

Visit my books page

Jim Thompson was a master at that.

You can open just about any Jim Thompson novel on the first page and find yourself drawn into his tale by the second sentence, sometimes even the first.

E.g.:

"I'd gotten out of my car and was running for the porch when I saw her. She was peering through the curtains of the door, and a flash of lightning lit up the dark glass for an instant, framing her face like a picture..."

(The opening of A Hell of a Woman by Jim Thompson).

Having said that, there are writers who've flouted that rule from time to time, indeed every rule going, and still produced amazingly readable works.

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov is an astounding comic novel in which even the index is funny. It's written in the form a review of a poem. The reviewer takes centre stage in his purported appraisal of the work of the poet, and he finds excuses in every line of the poet's magnum opus to discuss his own life story.

Borges uses a similar idea for his short story Pierre Menard, author of the Quixote.

This story envisages an author re-writing Don Quixote without changing a single word of it, and being credited with having created a better and more original novel than Cervantes.

Nabokov and Borges both adopt the persona of a bumptious literary critic for their works. This approach doesn't lend itself to an opening in which the reader is taken effortlessly to the meat of the story. But this hardly matters. These are works of genius that turn storywriting on its head and do it so successfully that you can only marvel at what the authors have achieved.

The take-home is this: when you're that good, the only rule that counts is that there are no rules.

See:

Do you want to write a story?

Visit my books page

Comments

Post a Comment