Working in a Morgue

My experience of working in a morgue is limited but illuminating.

Let me share it with you.

I left school when I was eighteen years old. I had a couple of

months to kill before I started a course in Architecture, so I got a job

working in a hospital as a porter. It was called St Luke’s Hospital, and it’s the

place where I was born.

Hospital Porters are the people who take food up to the wards, remove

the soiled laundry, and move patients around on wheeled stretchers, (or gurneys,

as you call them in America). Porters do most of the manual jobs that need to

be done in hospitals.

One day I was working on some boring menial task or other – I think

it might have been emptying the bins – when one of the permanent porters approached

me. His name was Stan.

“Jack, could you give me a hand with something, please?” He said.

Stan was middle-aged, overweight, and so unfit that he looked as if

he should have been occupying one of the hospital beds, rather than tending to

the needs of those who were in them. He was the kind of guy who sweated a lot

at the best of times, and in the overheated conditions of St Luke’s Hospital in

the height of summer, the sweat was pouring from him.

“Sure,” I told him. “I just

need to finish these bins then I’ll be right with you.”

He frowned and shook his head. I felt a shower of perspiration

spatter my face and fought the temptation to wipe it off.

“This job can’t wait,” he said. “You’ll have to leave the bins for

now and finish them later.”

I was curious to know what could possibly take precedent over

bin-emptying, given that it had been drummed into me how vital it was to

maintain clean conditions on the wards at all times.

“What do you want me to do?” I asked.

He took a handkerchief from his pocket and mopped his brow.

“Follow me,” he said mysteriously. “You’ll see.”

He led me along a glazed corridor and down a flight of steps to the

basement. Ahead of us there was a solitary door. He took hold of the handle and

hesitated before opening it. We went inside. The room we entered was different

to the rest of the hospital; it was cold and unsettling. We both felt it.

I looked around. All I could see was a wheeled stretcher with a

white sheet thrown over it. Stan grabbed the handles at one end of the

stretcher.

“You take the other end,” he said.

I did, and discovered that it was oddly heavy for an empty stretcher,

even with the two of us pushing it. We got it out of there quickly – Stan

didn’t want to linger, and nor did I – and we went upstairs to one of the

wards. One of the beds on the ward had curtains drawn around it, screening it

from view. We took the stretcher into the curtained area, and Stan removed the

sheet that had been covering it.

I saw then that it was a most unusual stretcher.

Rather than being flat, like a regular one, it was shaped like a

rectangular box the size of a coffin. The sheet that had been draped over it had

hidden the box from view, and given it the appearance of a normal wheeled

stretcher.

There were more surprises in store.

Stan showed me that the walls and lid of the box could be removed,

leaving a flatbed like you got on any other stretcher.

“Now comes the difficult bit, “he said.

“What do you mean?”

“We have to move this onto the trolley.”

He pulled the covers back from the bed we were next to, revealing

the face of an old man.

I knew instantly that he was dead.

He’d probably been alive only a short time before, yet his skin already

had a ghostly white pallor which, I must admit, I found most repellent.

He pulled back the covers fully, and I got to see a pair of legs

which were so thin, so white and so hairless that it was difficult to believe

that they could ever have belonged to a human being.

“Help me get ‘im on the stretcher,” said Stan.

We manoeuvred the body onto the flatbed of the stretcher. Next, we reassembled

the box around it, draped the sheet over the box, and we had what looked like

an empty gurney. We wheeled it back to the basement room we’d taken it from.

When we got there, Stan took a ledger and pen from a shelf.

“We ‘ave to check ‘is jewellery and teeth and write it down in ‘ere,

to make sure no fucker nicks it,” he said. “Could you do that for me lad? Could

you check ‘im for me while I write it down? I don’t like touching the dead ones.”

We opened up the box to reveal the body. I leaned over and

inspected its face. It had a ghastly grimace on it, which horrified me, but somehow

didn’t surprise me. I looked at Stan and he looked at me.

“Go on,” he said. “You need to look in its mouth.”

I touched the pale lips. They were cold. When I pulled them apart,

I had to grab the lower jaw and give it a tug in order to see all the teeth

properly. They were yellow-brown stained,

and amongst them there were two that were made of gold.

“Two gold teeth,” I said, quickly closing the mouth.

Stan noted it in the ledger.

“Check for a chain around ‘is neck.”

I parted the hospital gown that the body was wearing. There were

tufts of white hair sticking out of it near the neck, but nothing more.

“The wrists. Now check the wrists.”

I rolled back the sleeves from the spindly wrists and examined them.

There was nothing in those sleeves but skin and bone.

“Next we ‘ave to put ‘im away.”

He nodded with his head towards the far end, and for the first time

I noticed that an entire wall of the room was covered in small metal doors,

resembling the doors of many safes, each of which was perhaps two and a half foot

square.

We wheeled the trolley next to the wall, and Stan opened one of the

doors. A white mist rolled out from the void at the back of it. The mist was

followed by a chill in the air.

The void was the length of a man, and then some. Stan wound a

handle on our stretcher which raised the level of the flatbed to the same level

as the void at the back of the door. We rolled the body into the void on a

wheeled plate, and shut the door behind it.

We both got out of there very quickly, and we didn’t discuss what

we’d just done.

This was a procedure I repeated many times that summer. There was a

large geriatric unit in St Luke’s hospital, and many of the patients failed to

survive their stay there, providing me with plenty of visits to the morgue.

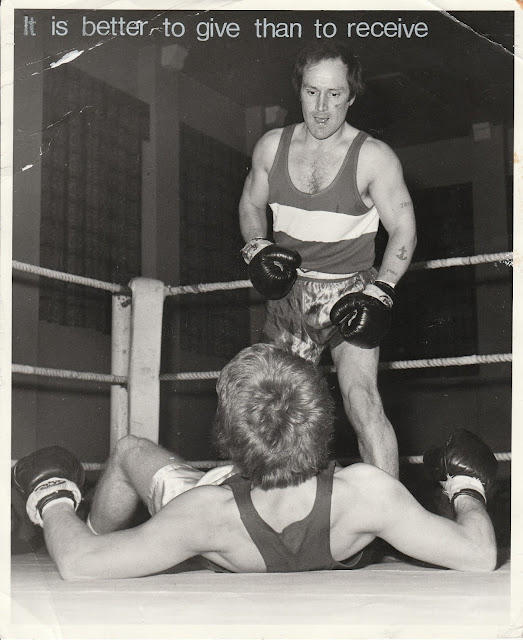

The photograph, by the way, is a picture of me that was taken that

summer, when I was aged eighteen and working as a hospital porter. It was taken

in what was once a well-known Huddersfield pub, called The Albion. Like so many

other things from my youth, it no longer exists. Nor does the hospital.

Thanks for your time,

Comments

Post a Comment